The opera world’s relationship with feminism is complicated. On the one hand, it constantly performs and celebrates works written by men in past centuries, which of course contain some distinctly outdated gender roles and values. On the other hand, as in the world of Shakespeare, today’s opera productions and scholarship can examine the beloved works from a feminist standpoint, sometimes critically, but at the same time celebrating proto-feminist themes, which are often surprisingly strong. Nowhere is this more evident than in modern stagings and commentary on the Mozart-Da Ponte operas, especially Le Nozze di Figaro. To many operagoers and opera scholars, Figaro’s proto-feminism is even more engaging and relevant than the themes of class conflict that made it radical in its day.

But just as some feminist Shakespeare scholars do, feminist opera scholars sometimes take a reductive view of the characters, especially the males. Repeatedly I’ve found critics and commentators so eager to celebrate Susanna and (to a lesser extent) the Countess that they seem to see nothing but flaws in the male characters. In their writing, the Count becomes a one-note villain with no complexity, and Figaro, the character whose subversive popularity once had Europe’s aristocracy feeling their necks, becomes just an accessory for Susanna who can’t do anything worthwhile himself. But not only does this misrepresent the opera, in my humble opinion it’s less feminist than an honest view of the piece would be.

Unquestionably, this opera does portray all its women as both smarter than and morally superior to all its men. I’m not arguing against it. But that very fact is both a blessing and a curse from my feminist viewpoint. It shouldn’t be a woman’s job to always be the smarter morally superior one; nor should it be her job to love a man with no redeeming qualities. The fact that Figaro and, yes, even the Count, do have redeeming qualities is important. So I’d like to offer a limited defense of both of Le Nozze di Figaro’s two leading men.

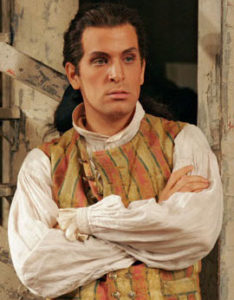

Figaro

The commentary I’ve read surrounding Mozart’s Figaro is different both from that surrounding Rossini’s Figaro and from that surrounding the Figaro of Beaumarchais’s original plays. This is no real surprise, since the character does take on different nuances in each interpreter’s hands. But more than any of the others, Mozart and Da Ponte’s Figaro seems to be viewed as a different character, and of all the Figaros he seems to be the least respected. Not in terms of Mozart’s music or Da Ponte’s writing, God forbid, but as a person. Beaumarchais’s Figaro is celebrated as the archetypal commedia dell’arte-style cunning servant made grander and fully human, a witty jack-of-all-trades who can think his way out of all adversity, a rebel against unjust authority, in fact an icon of satire and proto-revolutionary zeal, and superior in every way to his master the Count. Rossini’s Figaro, while a bit more one-dimensional and less of a social rebel, is similarly admired. But Mozart’s Figaro, while still liked and still praised for his humor and rebellious spirit, tends to be viewed as essentially a clueless, bumbling oaf. One who thinks he’s more cunning than he really is, but who would be lost without his much smarter and more competent bride Susanna.

This is understandable. Unlike in The Barber of Seville, where Figaro’s schemes are effective, only foiled by the young aristocratic lovers’ mistakes, and where his quick thinking ultimately saves the day, the sequel’s Figaro makes constant mistakes and wrong assumptions, and is constantly outshone in cleverness not only by Susanna, but the Countess too, in the classic trope of “women are wiser.” From his early failure to realize the Count’s designs on Susanna, to his contract with Marcellina that nearly costs him his marriage, to the collapse of his plan to fool the Count in Act II, to his belief that Susanna is unfaithful in Act IV, the sequel definitely deflates his ego. The opera probably does him even less favor than the play, since Da Ponte was forced to “defang” him politically to please the censors. Hence when he thinks the Count has seduced Susanna, instead of the insightful and scathing rant the play gives him about the aristocracy’s unfair privileges, he sings the wrongheaded, comically sexist aria “Aprite un po’ quegli occhi” about women’s deceit… making the audience want to slap him at the very moment when they would have cheered for him if his original speech were left intact.

Still, it’s reductive to label the Mozart/Da Ponte Figaro a clueless oaf. Commentators, especially feminists eager to highlight Susanna’s wonderfulness, seem to forget that her fiancé does anything competent at all.

So often people misremember the plot as “Figaro makes a hopelessly flawed plan to humiliate the Count, but after it inevitably fails, Susanna and the Countess make a better plan that works.” But this is only half-true. Figaro’s plan is never actually abandoned. The Countess and Susanna modify it, but the basic outline is still Figaro’s: Susanna pretends to accept the Count’s advances and invites him to meet her in the garden that night, but an imposter meets him in her place, and then the Countess “catches” him in the act of cheating. It’s a perfectly sound plan, it works, and it creates the opera’s happy ending. Figaro’s only mistakes are (a) to try to distract the Count from their intrigue by making him think the Countess is cheating, not predicting that the Count will confront her at the worst possible time, and (b) involving Cherubino, when the Count has reason to suspect that Cherubino is his wife’s “lover.” But neither of those mistakes is obvious. Even Susanna overlooks them at first; only the Countess has any early misgivings.

Susanna is one of the best-loved characters in all of opera and understandably so, but some operagoers become so infatuated with her that they give her the credit for other characters’ achievements. More than once I’ve seen Figaro’s entire plan attributed to her, or at least seen her credited with its modified version that has her switch clothes with the Countess. But the latter idea is really the Countess’s, who even dictates the letter Susanna sends to the Count, and is the one who encourages the nervous Susanna as they put the plan into action. Too many commentators not only reduce Figaro to “Susanna’s bumbling dolt of a fiancé” and Susanna herself to “the infallibly smart, feisty heroine,” they reduce the Countess to “the sweet, sad figure of the wronged wife,” ignoring her own intelligence and courage and their importance to the plot.

Susanna might be more practical and down-to-earth than Figaro, but she’s not portrayed as a schemer. Her brilliance lies in observation, wit, and improvising moment by moment, while Figaro and the Countess are the “idea people.” Figaro lays out the plan, the Countess fine-tunes the details and Susanna makes it all work in practice. To make a theatre analogy, Figaro is the playwright (fitting, since Beaumarchais’s Figaro is an ex-playwright in his backstory and has plenty of traits in common with Beaumarchais himself), the Countess is the director, and Susanna is the starring actress with a knack for invaluable ad-libs. Each of these three characters is smart in a different way; Figaro’s mistakes don’t stem from stupidity, but mostly from the fact that his schemes are so perfect in his mind that he overlooks potential real-world pitfalls. Hence the “women are wiser” trope comes into play and he relies on Susanna and the Countess. But feminist operagoers tend to forget that however “wiser” they might be, the ladies rely on him too. All three characters deserve credit for their victory in the end.

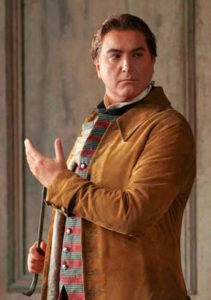

Count Almaviva

When thinking of the two skirt-chasing aristocratic baritones in the Mozart/DaPonte operas, I’ve repeatedly asked myself a question: Why is Count Almaviva forgiven, while Don Giovanni is condemned to hell?

Of course there are several possible answers. Some people might say “Because Beaumarchais’s play has the Count forgiven, while the legend of Don Juan condemns the Don to hell. Mozart and Da Ponte just took the stories they were given, without aiming for philosophical consistency.” Others insist that we the audience are supposed to forgive the Don and view his punishment as unfair. Still others argue that we’re supposed to be dissatisfied with Figaro’s ending and view the Count as unworthy of his wife’s forgiveness. Goodness knows, feminism and the #MeToo movement make it tempting to write off both men as pieces of scum. If anything, most operagoers seem to despise the Count more than they do the Don. This is probably because Figaro, Susanna, the Countess and Cherubino are more likeable than the Don’s morally grayer victims, because the Count lacks the Don’s sheer courage and audacity while the Don lacks the Count’s hypocritical jealous rages toward his wife, and because the Don has a mythic stature that makes the Count seem small and petty by comparison.

But if we take both operas’ finales at face value, assume we’re meant to approve of both outcomes, assume that Mozart and Da Ponte meant for both characters to criticize the aristocracy’s womanizing and power-abuse, and assume philosophical consistency between the two operas, then why is the Count forgiven while the Don goes to hell? Even though the Count is more of a hypocrite, more of a petty bully, and has more likeable victims than the Don? Why the difference?

I’d like to offer some possible answers.

First of all, the Count doesn’t kill anyone. Some people might argue that this is the most important difference: the Don’s crime that leads directly to his doom is killing the Commendatore. Granted, he only does it reluctantly, in self-defense, and in a fair fight; and granted, the Count draws his sword intending to kill Cherubino when he thinks he’s slept with the Countess and is hiding in her dressing room. For those reasons, I don’t rank this difference as important as others I’ll discuss. Still, only the Don has blood on his hands in the end, and the fact that the fatal duel takes place because he tried to rape Donna Anna makes it worse.

This leads us to the next key difference: the Count never tries to rape anyone. While commentators sometimes accuse him of wanting to “rape” Susanna by legally forcing her to accept the droit du segneur, his seduction and bribery efforts seem to imply that he wants her to be willing; he uses the droit more as an excuse to seduce her than as a method of force. True, his threatening to make Figaro marry Marcellina if she refuses muddies the waters, but it’s still not the same as a literal, physical rape attempt. And while Don Giovanni’s real-world admirers often deny that their hero ever attempts rape (i.e. insisting that the Donna Anna incident was consensual, ignoring that even Leporello calls it force, and that the Zerlina incident is just “rejected wooing”), those claims are always doubtful.

The Count himself would also probably point out that he never abandons anyone, and that unlike Leporello, his servants are “well treated.” Cheating on his wife isn’t the same as leaving a wife after three days and then treating her as just another ex-conquest. Trying to seduce his female servants and cuckold Figaro, yet still feeding, clothing and paying them well and only raging at them when he genuinely feels betrayed, isn’t the same as the Don’s dragging Leporello through dangerous misadventures, keeping him underfed and short of sleep, raging and threatening him over minor disagreements and sometimes scaring him out of his wits just for laughs. More enlightened viewpoints and the #MeToo movement would debate whether any of those differences give the Count moral high ground or not, but the Count himself would definitely cite those differences in his defense.

The Count also has a conscience that the Don lacks. In passing moments, both to others and to himself in private, he admits that what he does is wrong and expresses remorse. Of course “he briefly regrets his sins, but then goes on committing them anyway” is hardly admirable, but it still sets him apart from the remorseless Don, who never admits that his life is less than morally upstanding. The moment in Figaro’s finale when the Countess forgives her husband is preceded by the Count kneeling before her, in front of his servants and social inferiors, and begging her forgiveness. Of course it’s questionable how long that repentance will last, but it’s also safe to say that the Don would never debase himself that way. Not unless he were feigning it to manipulate someone.

Last but not least, and expanding on the above, the Count has an emotional sincerity and vulnerability that the Don never even approaches. We know from The Barber of Seville that he truly loved Rosina when they married, or at least believed he did, and he still shows her sporadic affection. His infatuation with Susanna feels genuine too. Whether it’s real love or just lust is debatable, but regardless, he sings of “sighing” for her and is genuinely distressed that she doesn’t return his feelings, not just annoyed. Compare this to the Don, who treats women only as playthings and responds to each thwarted conquest by cold-bloodedly moving on to the next. And while the Count’s temper is uglier than the Don’s, it only flairs when he feels genuinely wronged, whereas the Don uses his temper as a tool to get his way. Commentators always highlight what an arrogant, vengeful and frightening aria “Vedro, mentr’io sospiro” is, and of course they’re right, but it’s also a very human and raw expression of frustrated longing. Don Giovanni, fascinating figure though he is, has no such moment of emotional complexity.

Does any of the above excuse the Count’s behavior? Absolutely not! But all these different nuances beneath his superficially Don Giovanni-like veneer just might explain why he’s forgiven in the end. Not only why the Countess forgives him, but why Mozart, Da Ponte and Beaumarchais seem to endorse it. For all his skirt-chasing and petty bullying, he never commits real crimes, isn’t an outright abuser (not by his era’s standards, at least), and has the capacity for real remorse, pain and, just maybe, love: a capacity Don Giovanni never shows. Whether or not those qualities make him worthy of forgiveness, they’re worth noticing.

Neither Figaro’s intelligence nor the Count’s complexity diminishes Susanna or the Countess whatsoever. Arguably, just the opposite is true. Would it really be feminist for Susanna to marry a man unworthy of her respect, or for the Countess to unconditionally love and forgive a one-note villain of a husband? If anything, it serves the ladies better to highlight the positive traits in their men than to highlight their flaws alone.

Доброе утро Розыгрыш призовых вещей №962 Забрать >> https://forms.gle/9VM37p3L3AEdWwuh9?hs=59453dc06e806a8e491aa428a8c03d43&

February 22nd, 2023 at 00:25

suvol9